“We own a few books where the side (fore-edge) of the text block is not even. The 1st set amount of the pages are about 1/16” out farther than the 2nd set. The 3rd set is about 1/16” out farther than the 2nd set but equal to the 1st set. The 4th set is the same as the 2nd, and so on. It is as if each small binding section of pages was cut at 2 different widths. Is there a name for this type of edge, or is it an error in binding?”

Sometimes we receive questions from not only book printers, but from individuals interested in bookbinding. If it gets “technical,” this former teacher has the privilege and pleasure of answering them. Here is one such question I received earlier this month:

“We own a few books where the side (fore-edge) of the text block is not even. The 1st set amount of the pages are about 1/16” out farther than the 2nd set. The 3rd set is about 1/16” out farther than the 2nd set but equal to the 1st set. The 4th set is the same as the 2nd, and so on. It is as if each small binding section of pages was cut at 2 different widths. Is there a name for this type of edge, or is it an error in binding?”

Let us try to understand this phenomenon.

Deckle Edges

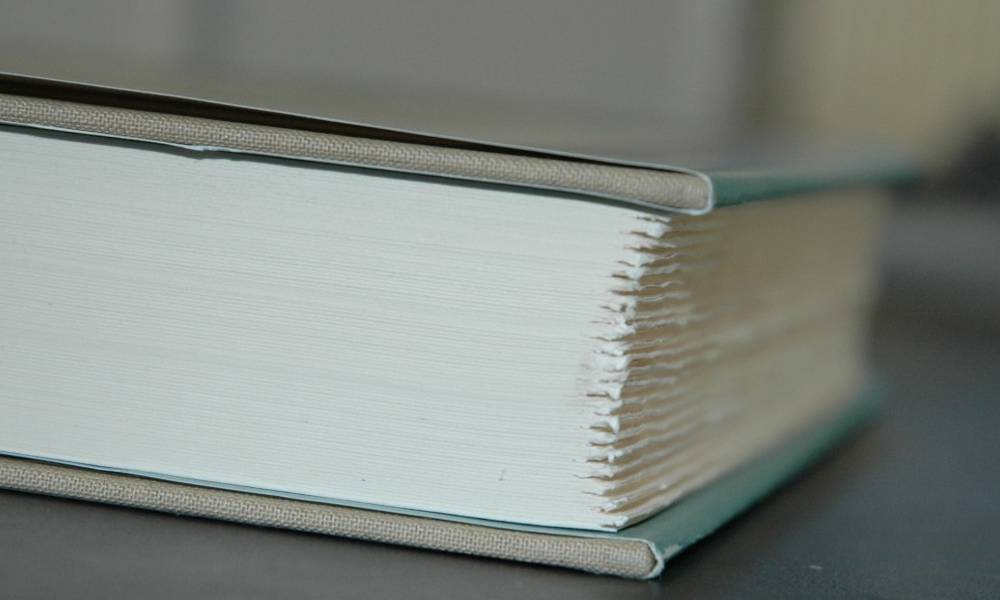

As we are all aware, earlier papers were made by hand. In this operation, the paper pulp is flowing between the frame and the deckle of the mould. This hand casting operation created unusual, beautiful edges. When papers were made by machine, the paper manufacturers tried to imitate that feature by means of a jet of water or air. Other deckle edges can be formed on dry sheets by means of tearing, cutting with a special type of knife, sand blasting or sawing.

In earlier book manufacturing, there were no machines available for trimming the edges. As a result, the folded signatures (sections) were left untrimmed—a tradition carried on until a few decades ago. As a hand bookbinder, I have bound many French books with untrimmed signatures or deckle edges. Such untrimmed edges became popular in the late 19th century and lasted to almost the 1990s. For publishers, we had to imitate such rough deckle fore-edges on common machine made papers for many best-selling books. On folding machines and web-printing presses, we used special, dull knives to create such an effect, with the results, that virtually every single sheet varied in its dimension on the fore edge. Librarians did not appreciate that trend as such bindings collected dust, were unsightly (to some) and difficult to turn.

Having explained you the process where we tried to create the deckle edges as an ornamental feature, now let us look at a case where these are developed unintentionally.

Web-Printed Variables

Book and catalogue offset printing is done in sections of 16, 24, and 32 page configurations. One of the largest printing companies on this continent printed a thick Gun Catalogue. A few days

after trimming a smooth edge, the Q.C. Manager sent samples to the RIT book testing laboratory and stated that they are unable to figure out this “phenomenon.” Their client rightfully objected to that “saw-toothed” fore-edge and threatened to reject the entire 100,000+ order.

What was going-on? The answer is simple. When using heat-set web offset printing, printers use one large mill-roll of paper after the other. Each section is printed individually and then stored in a warehouse. It often takes days, and even weeks to print such a large order. Most often, printers operate their expensive web presses around the clock, which mean each crew may have a different idea of how to dry the ink, especially large, solid areas. The crews may use different heat settings. Such fluctuations in the paper and in the printing processes will have some consequences. After trimming, the paper is picking up moisture and then wants to grow back into its final “resting” position. Different heat settings, storage conditions and moisture content in each individual section then results in uneven growths. This description is an experience from an actual consulting assignment where, as is most often the case, the binder gets blamed!

Older books often feature untrimmed, rough edges. One large German law-book printing and hardcover binding company I visited solved this problem with trimming the book blocks twice. First they trimmed open the folds. Then they let the book blocks rest for 72 hours, giving the paper a chance to adjust to its environment. A three-knife trimmer in front of their hardcover binding line then did the final trims. Those were the smoothest book edges I have ever had the pleasure to observe.

Communications in regards to Trimming

As we now know, a book with genuine deckle edges is one a bibliophile will always treasure. Some time ago, a library binder in the Midwest (no longer in business) received such a valuable

book from a rare book library with the instructions “Save the Deckle Edges.”

When the rebound book came back to the library, the librarian noticed that contrary to their instructions, all three sides were trimmed smoothly. When the librarian lifted the cover, she noticed an envelope. It contained the “saved” deckle edges!